|

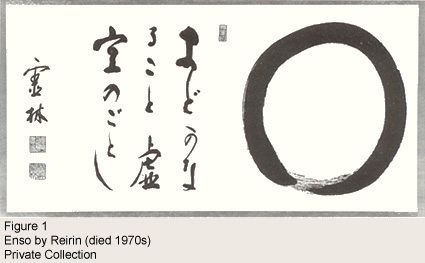

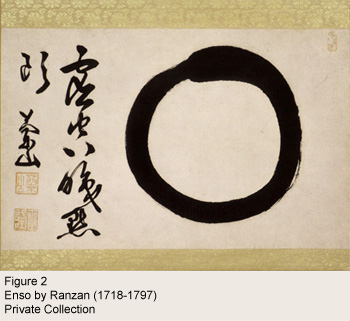

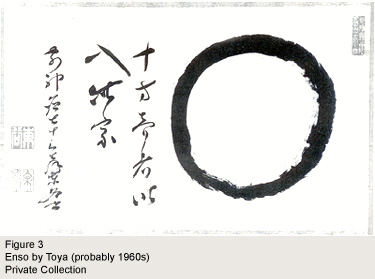

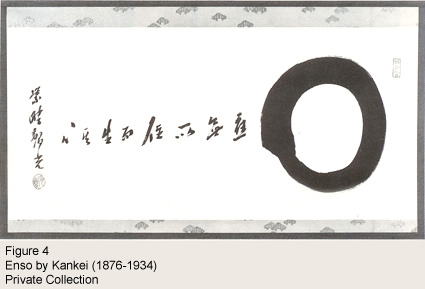

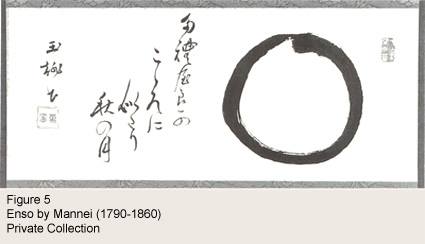

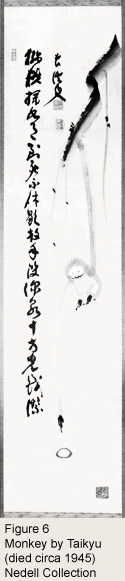

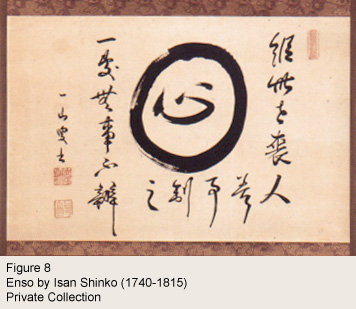

ZEN ART IS SPIRITUAL art in its purest sense. It was done not by professional artists, but by Zen monks and nuns who spent extremely disciplined lives of meditation, in a search for enlightenment and awakening to the true nature of reality. That they were painting from their own personal knowledge of this reality, rather than from doctrines handed down, is the very foundation of this art-form's compelling power. It is believed in Japan that the character and spiritual realization of the monk or nun are transmitted into the painting itself. In 1707, a young monk named Hakuin saw the rustic calligraphy of an old Zen master that greatly moved him. Although his own calligraphy may have looked more polished because of his intensive brushwork practice, it was painfully obvious to him that his work did not reflect inner realization. Hakuin saw that in the calligraphy of the old master: The virtue shines—skill is not important. He burned his brushes, redoubled his efforts in Zen practice, and did not seriously begin calligraphy again for another forty years. All Zen art grows out of just such a tradition: years of discipline and meditation, the quest for awakening and enlightenment. Zen art remains a living tradition to this day, although it has strong and deep roots in the past. |

|