Reflections on Zenga

Stephen Addiss,

The University of Richmond

It has now been thirty-five years since I first began to study Zenga, the word that describes Zen painting and calligraphy from 1600 to the present day. There have been many changes in the understanding and acceptance of Zenga during that time, both in Japan and the outside world, prompting me to offer my recent reflections on the subject.

When I first became interested in Zenga, it was regarded somewhat suspiciously by most academics. It did not have the prestige of Muromachi ink painting, which was highly admired both for its evocative nature and for the high skill levels of the artists, and it seemed to fall somewhere outside the mainstream of Japanese art of the Edo period and later. There were several Japanese experts in Zenga, including Takeuchi Naoji (who wrote a splendid book on Hakuin while working at the Tokyo National Museum), but Zenga did not often appear in standard books on Japanese art or Japanese painting, and one connoisseur that I knew in Kyoto went so far as to say it was "not art." Why was this so?

First, Zenga did not often show the technical expertise that had graced Muromachi ink painting, when artists such as Sesshu were to some extent professional painters. Because of the high demand for Zen art by shoguns, daimyo, wealthy samurai and merchants (Zen paintings were even used in trade with China), Zen art was done by monks who could devote most of their time to this occupation and often worked in temple ateliers. In contrast, the monks who created Zenga after 1600 were almost always Zen Masters who were primarily devoted to supervising temples and teaching students. There was no longer a broad scope of patronage for this art, but instead the works were given directly to followers of the Zen Masters, including both monks and lay pupils. As a result, the paintings tended to become much more simple, and the Zen message more important, than had been true before 1600.

Second, Zen after 1600 did not hold the great cultural sway that it had been given in the Muromachi period. Not that all or most of the Japanese elite- government leaders, samurai, and rich merchants- had been believers in Zen, since Pure Land and Esoteric sects were highly patronized. Nevertheless, the cultural ideals associated with Zen had dominated Japanese life; education, government advising, the tea ceremony, and even foreign trade were in the hands of Zen monks. After the Edo period began, however, the Japanese government gradually turned to Confucian scholars for its advisors and teachers, and Zen became just one element of a surprisingly pluralistic society. For an example in the world of art, there was now patronage for Kano and Unkoku painting by the shogunate; Tosa painting by courtiers; Rimpa and Maruyama-Shijo painting by merchants; Nanga (literati) painting by educated Confucians; traditional Buddhist painting by non-Zen temple monks; and ukiyo-e painting by townsmen. In the view of many scholars, Zenga was a minor and somewhat peculiar offshoot of what had once been a glorious Japanese artistic tradition.

In the past thirty-five years, that view has changed. Instead of demeaning Zenga for what it was not, it began to be admired for what it was, the direct visual expression of the most important Zen Masters of the past four hundred years. It is rare in history that the leading religious leaders are also the artists; imagine if the pope had painted the Sistine Chapel himself instead of asking Michelangelo! But whether one studies Zen history or Zen art of the past four hundred years, the same names emerge as the most significant masters, with Hakuin at the forefront and also including Takuan, Bankei, and Torei. Viewing Zenga therefore becomes a form of communication with the great Zen Masters of recent centuries. Furthermore, bold simplicity instead of stress on technical skill can lead to great immediacy of impact, and Zen Masters were not shy about using dramatic brushwork, popular subjects such as animals and folklore themes, and even humor in order to make their art accessible to the public.

Another change that I have seen take place is the increased interest in calligraphy, including Zen calligraphy, by younger collectors, scholars, and the broader art public. What was once considered too arcane for Westerners is now a legitimate field of interest, study, and enjoyment. Perhaps the background in abstract expressionism and action painting, that we now take for granted as part of our heritage, has influenced this change; there is no question that calligraphy is now a good deal more popular in the West than ever before.

The study of Zen art has also interacted with historical studies of Zen. Scholars in recent decades have rediscovered the importance of Hakuin, Bankei and Torei in religious history, and there has also been a movement to downplay the descriptive and philosophical texts by such writers as D. T. Suzuki in favor of studying Zen as an ongoing institution, depending upon temple training and direct transmission from Master to pupil for its core of being. In the Rinzai sect, for example, it has become clear that the training methods established by Hakuin and his pupils have been absolutely vital to the continuation of Zen as an active force in Japanese religious life. The result of these changes is that Zenga, including both painting and calligraphy, is now appearing more and more often in standard books on Japanese art and culture, is being shown in large-scale exhibitions, and is being collected seriously by both private connoisseurs and (more slowly) by public institutions. Westerners have played a leading part in this development; Kurt Brasch was an influential pioneering scholar, and his book Zenga (published in both German and Japanese) is still an important text in the field. I myself was pleased that my book The "Art of Zen" was translated into French ("L'art Zen"), and that it has recently been reissued in paperback.

How else has the understanding of Zenga changed? One may ask whether there has been some reconsideration concerning which Zen monk-artists were the most important. In general, I would have to answer that the previously well-known names have remained in the forefront, including Takuan, Bankei, Hakuin, and Torei as well as Sengai, Ryokan, and Jiun (the latter actually a Shingon monk who studied Zen and created powerful Zenga). However, another development has taken place recently that is parallel to what has happened in the study of other Japanese arts: there has been a greatly increased attention to the works of the past century.

For example, we have recently witnessed a boom in interest for the paintings and calligraphy of Nantembo (1839-1925), who now must be considered among the leading historical monk-artists of Japan. Recently the young American scholar Audrey Yoshiko Seo has studied other modern masters, and her work now appears in a major exhibition and book entitled "The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen" (see the end of this article for information). In her research she has discovered that there have been many fascinating and creative Zen Masters during this century that deserve to stand with their artistic and spiritual ancestors, including Mokurai (1854-1930), Yamamoto Gempo (1867-1963), Seki Seisetsu (1877-1945), Deiryu (1895-1954), and Shibayama (1894-1974). Her exhibition ends with a contemporary Zen Master who creates extremely strong calligraphy, Fukushima Keido (born 1933), currently the abbot of Tofuku-ji in Kyoto.

I was invited to write one of the chapters in Dr. Seo's book, and so I studied Soto sect monastics of this century including Nishiari Bokuzan (1821-1910) as well as the wandering monk and haiku poet Santoka (1882-1940). Perhaps most fascinating of all was the Zen nun Kojima Kendo (1898-1995), who successfully fought for the rights of female monastics in the Soto sect, led a training center and taught many followers, founded an orphanage after the Second World War, and took up calligraphy after she broke her hip at age ninety-two.

|

|

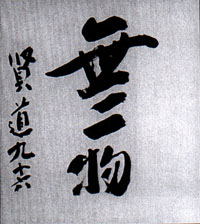

As it happens, Zenga has usually been done by Masters at an advanced age (Hakuin's "early works" are those done in his sixties), but I do not know of a parallel to Kojima creating works almost entirely in her mid-nineties. She worked most frequently on the square poem-cards called shikishi, and one example from her ninety-sixth year shows the strength of spirit that she maintained throughout her long life (fig. 1). The text is the Zen phrase "Mu ichi butsu (Not one thing)" and Kojima keeps a steady level of negative space within and well as between the three characters, so that the three words become unified. But is this calligraphy "one thing" or "not one thing"? |

|

Before closing, it may be instructive to compare traditional Zenga with a more recent example of the same subject. Portraits of Daruma (Bodhidharma), the first patriarch of Zen, represent the homage of Zen Masters to their spiritual ancestor, but they also signify each monk-artist's understanding and visualization of meditation. Hakuin Ekaku's image of Daruma, painted a few years before his death in 1768 (fig. 2), has a brooding intensity that is enlivened by subtle ranges of ink tones. The body of the patriarch is simply rendered in a few strokes (including a hint of the character for heart/mind at his throat), so our attention is directed to the face, and particularly the wide inwardly-staring eyes. The inscription consists of two four-character lines attributed to Daruma that sum up the Zen experience:

|

|

|

|

In comparison to the image by Hakuin, the Daruma by Yuzen Gentatsu (also known as Sanshoken, 1842-1918) follows the same compositional scheme but expresses a very different mood (fig. 3). Heavy strokes of black ink, mostly wet and fuzzing, describe the robe, the eyebrows, eyes, and the sides of Daruma's mouth, while thinner strokes in light gray complete the face of the patriarch. The inscription is merely four characters:

|

While Hakuin's Daruma is fierce, Yuzen's seems more melancholy. The eyebrows slant down rather than upwards, and the figure seems hunched into his robe in the lower part of the composition rather than dominating the center. Yet Yuzen's work has great expressive power which testifies to his own Zen experience. Living in an age when Buddhism was struggling, he was one of the Zen Masters who helped continue the traditionally strict training of monks while rebuilding temples that had fallen into serious disrepair during the government suppression of Buddhism in the early Meiji period. Yuzen's life was difficult, and his view of the rapidly changing world around him is one of the elements that is expressed in his paintings. Nevertheless, his own personality and profound Zen experiences are the most significant factors in his works that combine power, depth of spirit, and a wonderful touch of humor. The future of Zenga seems to be assured. Masters such as Fukushima Keido continue to find that ink painting and calligraphy offer an opportunity for a traditional Zen activity that reaches through time and space to viewers in many parts of the world. The exhibition prepared by Audrey Yoshiko Seo will bring a fascinating century of Zen art to the public, and I have no doubt that future generations of collectors and scholars will find Zenga to be a marvelous field of study and enjoyment.

The book-catalogue "The Art of Twentieth Century Zen" is published by Shambhala Publications, Boston

Captions:

1. Kojima Kendo (1898-1995), Mu Ichi Butsu Shikishi (1993) Ink on paper, 26.8 x 24 cm. Private Collection

2. Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768), Daruma Ink on paper, 128.8 x 55.3 cm. Chikusei Collection

3. Yuzen Gentatsu (1841-1918), Daruma Ink on paper, 80.2 x 32.5 cm. Hosei-an Collection