"My play

with brush and ink

is not

calligraphy nor painting;

yet unknowing

people mistakenly think:

this is

calligraphy, this is painting."

Sengai

Gibon (1750-1837)

THE

APPRECIATION

OF ZEN ART

John Stevens

THE

EARLIEST reference to Zen brushwork occurs in the Platform

Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, a text which relates the life and teaching

of the illustrious Chinese master Hui-neng (638-713). Buddhist scenes,

composed in accordance to canonical dictates, were to be painted on the walls

of the monastery in which Huineng was laboring as a lay monk. At midnight the

chief priest sneaked into the hall and brushed a Buddhist verse on the white

wall. After viewing the calligraphy the next morning, the abbot dismissed the

commissioned artist with these words: "I've decided not to have the walls

painted after all. As the Diamond Sutra states

'All images everywhere are unreal and false."' Evidently fearing that his

disciples would adhere too closely to the realistic pictures, the abbot

thought a stark verse in black ink set against a white wall better suited to

awaken the mind.

Thereafter,

art was used by Chinese and Japanese Buddhists to reveal the essence, rather

than merely the form of things, through the use of bold lines, abbreviated

brushwork, and dynamic imagery—a unique genre now known as Zen art.

Although

the seeds of Zen painting and calligraphy were sown in China, this art form

attained full flower in Japan. Masterpieces of Chinese Ch'an (Zen) art by such

monks as Ch'an-yueh, Liang K'ai, Yu Chien, Mu Ch'i, Chi-weng, Yin-t'o-lo and

I-shan 1-ning were enthusiastically imported to Japan during the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries and a number of native artists, for example Kao Sonen and

Mokuan Reiun, studied on the mainland. Building on that base, Japanese monks

such as Josetsu, Shubun, and somewhat later Sesshu Toyo and Ikkyu Sojun

produced splendid examples of classical Zen art; eventually Zenga became one

of the most important Japanese art forms, appreciated the world over for its

originality and distinctive flavor.

Early

Zen in Japan was a religion for cultured aristocrats and powerful fords but by

the fifteenth century Zen priests and nuns became actively concerned with the

welfare of common folk. The democratization of Zen had a marked effect on

painting and calligraphy, and the scope of Zen art was dramatically expanded.

Hakuin

and Sengai, the two greatest Zen artists, employed painting and calligraphy as

visual sermons (eseppo) to teach the hundreds of people, high and low,

that gathered around them. Both of the masters drew inspiration from other

schools of Buddhism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Taoism, folk religion, and

scenes from everyday life; their calligraphy too embraced much more than

quotes from the Sutras and Patriarchs—nursery rhymes, popular ballads,

satirical verse, even bawdy songs from the red-light districts could convey

Buddhist truths. Zen art thus became all-inclusive: anything could be the

subject of a visual sermon.

Following

the example of Hakuin and Sengai it became de

rigueur for Zen masters to do much of their teaching through the medium of

brush and ink; a tradition that continues to the present day. In many ways,

Japanese Zen art parallels the Tibetan Buddhist concept of termas

(hidden treasures).

According

to Tibetan legends, the guru Padmasambhava hid thousands of texts all over the

country to be discovered later when the time was ripe for their propagation.

Whether or not this is literally true, during the persecution of Buddhism in

Tibet during the ninth century, a large number of religious texts and articles

were in fact hidden in caves, under rocks, inside walls, and other secret

places to prevent their destruction, and over the centuries such treasures

were gradually recovered. Similarly in Japan during this century, devotees of

Zen art have uncovered thousands of magnificent pieces locked away in temple

store-rooms, sitting forgotten on shelves in private homes, kept in drawers by

indifferent art dealers, or left uncatalogued in museums. The illustrations in

this article are largely comprised of such discoveries. Significantly, these

pieces, some unseen for centuries but still bearing a message as fresh and

forceful as when first delivered, are reappearing just as it is possible to

display them throughout the world by means of modern print technology.

While

the primary purpose of Zen painting and calligraphy is to instruct and

inspire, it does have a special set of aesthetic principles; indeed, the best

Zen art is true, beneficial, and beautiful a combination of deep insight and

superior technique. The freshness, directness, and liveliness of Zen painting

and calligraphy imbue it with a charm that few devotees of Japanese art can

resist.

|

|

The aesthetics of Zen art are difficult to categorize. Zen artists follow the method of no-method and, in that sense, Zen painting and calligraphy is anti-art: not created for purely aesthetic effect and beyond the normal categories of beautiful or ugly. As an unadorned "painting of the mind" true Zen art is created in the here and now encounter of the brush, ink, and paper and if it has drips or splashes on it so much the better! Zen painting and calligraphy can also be thought of as folk art. |

|

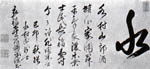

One of the finest

examples of Zen calligraphy ever brushed (Figure 1) is a set of scrolls

written by Ryokan (1758-1831) for an illiterate farmer: i-ro-ha,

ichi-ni-san (a-b-c, one-two-three). |

|

Certain

commentators have characterized Zen art as being asymmetrical, simple,

monochromatic, and austerely sublime; this, however, ignores the fact that

there exist perfectly round Zen circles, full-color painted "operas with

huge casts", and delightful cartoons with more than a touch of eroticism.

Actually, the most important element of Zen art is the degree of bokki present in the work. Bokki, "the ki projected into the

ink", activates the brushstrokes ("lines of the heart"). By

contemplating the clarity, vigor, intensity, extension, suppleness, scale, and

sensitivity of the brushstrokes, the artist's presence of mind and level of

enlightenment is made palpable. By way of illustration, consider the following

examples.

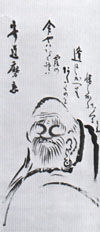

Daruma,

the legendary Grand Patriarch of Zen Buddhism, symbolizes penetrating insight,

self-reliance, and immediate awakening. The First Patriarch is the favorite

subject of Zen artists, a spiritual self-portrait as we can see in the five

illustrations presented here (Figures A, 2, 3, 4, 5); although the

subject is the same, the respective treatments are completely different,

reflecting the unique Zen style of each individual artist. This particular

style of Daruma is known as hanshz'n-daruma

(half-body Daruma); as an embodiment of the universe Daruma's entire form

is too big to capture on paper, and part of him remains hidden from the view

of unenlightened worldlings.

|

|

Temple life and religious ceremony was not for free-spirited Fugai Ekun (1568-1655); he spent most of his days on the road or living in caves where he obtained provisions in exchange for his paintings. Despite his vagabond life, or perhaps because of it, Fugai was a remarkably polished artist. Firmly constructed and finely textured, the brushstrokes of Fugai's Daruma (Figure A) are extremely clear and luminous. |

There is a powerful undercurrent of

stability, unostentatious refinement, and vitality. The vibrant bokki brings

this Daruma to life and one can sense the calm intensity of the Patriarch as

he gazes steadily past the viewer, taking in all the wonders that ordinary

people, preoccupied with their own affairs, overlook. An interesting feature

of Fugai's work is his frequent placement of his seal and signature behind his

Darumas and Hoteis, suggesting perhaps that the artist, too, is peering over

the shoulder of his creation at the viewer.

It is impossible to convey the overwhelming presence of this monster Daruma (Figure 2) by Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768). The painting itself is over seven feet in height and nearly five feet in width; mounted on an enormous scroll it covers an entire wall. The sixty-seven year old master marshaled all of his resources to produce this tremendous display of physical strength and spiritual power. The thick brushstrokes are bold, substantial and charged with energy. Note that the Patriarch's eyes are fixed on the viewer; as Hakuin wrote on some of his other Darumas, "I've always got my eyes on you!" |

|

The

viewer is literally forced to look within and "wake up". Such was

Hakuin-style Zen-demanding, forceful, expansive, and concrete. The inscription

reads: "Son of an Indian prince, Dharma-heir of Priest Hannyatara, he is

a rough looking fellow, full of wild determination."

|

|

At

first glance, Sengai Gibon's (1750-1837) happy-go-lucky Daruma (Figure 3)

appears to be the exact opposite of Hakuin's intent Patriarch. The kindly old

fellow smiles to himself, content to let things come and go as they please.

Critics have complained of Sengai's lightheartedness and cartoon-like

brushwork, but on closer examination Sengai's Daruma is found to be more

mature, older and wiser than the versions of other artists. The soft, lustrous

brushstrokes are full of warmth, contentment, and well-being. The accompanying

inscription, "Entrust yourself to Daruma. What is life? A drop of dew. When you meet this rascal, give it back without regret", indicates that

one must be unattached to all things, even Buddhism. Like all of his best

pieces, this painting originates in the realm of pure and uninhibited joy. |

Above all, the one factor that distinguishes Zenga from all other forms of religious art is its burnout, indeed irreverence. This Daruma (Figure 4) by Gako (Tengen Chiben 1737-1805), a student of the Hakuin school, resembles that of the master but the inscription contains a risque pun: "He peers into aeons with his clear eyed gaze. YES!! Dark willows, bright flowers... Dark willows, bright flowers" was originally a Zen metaphor for Buddha-nature but then it became a euphemism for pleasure quarters. The slang nickname for courtesan was "daruma" because they were like the legless Daruma toy dolls that always sprang up, ready for more, each time they were placed on their backs. In short, Gako tells the viewer that Daruma may as well be encountered in a brothel as in a monastery, and that one should not seek him exclusively in religious edifices. |

|

In keeping

with that theme, Gako's Daruma appears rather cagey; wide-eyed and alert, this

Daruma is impossible to deceive. However, he seems more tolerant and

understanding of human frailties than Hakuin's fierce Patriarchs. Regarding

the bokki, the large stroke forming Daruma's robe is brushed decisively

without a trace of stagnation and the eyes are bright and fresh.

|

|

Nanzan

Koryo (1756-1839) was Sengai's "Dharmabrother", related to the same

master; similar to Sengai, Nanzan enjoyed mingling with common folk, drinking

sake, and brushing Zen art. His mighty Daruma (Figure 5), glaring sharply to

the side in order to repel any approaching challenges to his serenity, is more

artistically composed than that of Sengai and is much larger in scale bigger

than life-size. This masculine, muscular Daruma fills the paper, assuming an

assertive, no-nonsense stance and it is hard to believe that such a vigorous

Daruma sprang to life from the brush of an eighty-three year old monk. As aficionados of' Zen art know well, this type of lively brushwork is

a bracing stimulant that refreshes and energizes the viewer. |

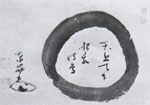

Next to paintings of Daruma, Zen circles (enso) are the favorite subjects of Zen artists. In addition to suggesting infinity, Zen circles also represent the moonmind of enlightment, the wheel of life, emptiness, a mirror, ultra-abbreviated Darumas, and even rice cakes; frequently the accompanying inscription on an enso asks, "What is this?", leaving the answer up to the viewer.

|

In this enso (Figure 6) Torei Enji (1721-1792) has drawn the universe. The brushstroke forming the circle is perfectly controlled, firm, steady, and somewhat reserved, much like Torei himself. The bokki is calm and clear. Inside the circle, Torei calligraphed Buddha's dramatic declaration at birth: "In heaven and on earth I alone am the Honored One." |

|

The four characters

"heaven-above-heaven-below" form a vertical axis to the side;

"only-I" is slightly off center and "honored-one" is

placed a bit down to the left. The inscription is thus a schematic

representation of human life: set between the poles of heaven and earth,

unique but not solitary. (Notice also the skilful placement of the first

"heaven" character solidly above "above" and then the

smooth shift to a cursive "heaven" character that flows down to

"down".) Other interpretations of this enso include "All of us

share the same nature as Buddha and can aspire to a similar

enlightenment" and "The universe is not outside oneself but

within!"

|

|

On

occasion, Zen artists combine Daruma and enso into one image as we see in this

piece (Figure 7) by Seiin Onjiku (1767 -1830). Normally with such an

inscription: "Who said, 'My heart is like the autumn moon?"' The

enso would be placed at the top of the paper; here, however, Seiin has set the

moon-mind at the bottom to represent Daruma "wall-gazing" (mempeki),

illumined by the moonbeams of enlightenment. Further, the inscription

reminds us that, despite vast differences in time and place, the minds of the

Patriarch, the Chinese poet Han-shan (to whom the verse refers), the Japanese

monk who created the painting, and that of the modern viewer are essentially

the same. Totally unaffected, Seiin's brushwork is soft and warm and the bokki

radiates gentle light. |

|

Next we have a marvelous visual sermon by Hakuin (Figure 8). The treasure boat of popular folklore is piloted by Fukuroruju, the God of Longevity (whose face resembles that of the artist). The boat itself is cleverly formed by the character kotobuki (long life) and contains the four symbols of good fortune: (1) lucky raincoat; (2) straw hat (representing the gift of invisibility from thieves and tax collectors); (3) magic mallet (the Far East version of Aladdin's Lamp); and (4) treasure bag. |

|

The inscription, which dances above the boat, states, "Those who are

loyal to their lord and devoted to their elders will be represented with this

raincoat, hat, mallet, and bag." The best way to steer through the rapids

of life is to board this ship as soon as it is launched one who is sincere in

his or her dealings with fellow human beings will naturally be blessed with

wealth and good fortune. The composition of the painting is light, bright, and

buoyant (notice how high the boat rides on the waves) while the message is

deep and universal.

|

|

This Zen painting by Taikan Monju (1766-1842) of a puppet show (Figure 9)—a theme first popularized by Hakuin—epitomises the essence of e-seppo. A puppeteer is performing a morality play on the filial piety of a poor Chinese peasant named Kakukyo. |

The

inscription relates the tale: "There was not enough food to feed both

Kakukyo's aged mother and infant son. Thinking to himself, 'I can always make

more children, but I only have one mother,' Kakukyo and his wife tearfully

decided to bury their child. When Kakukyo began digging a grave, he found a

pot of gold hidden in that spot. They were now rich and lived happily ever

after." The story concludes with this moral:

"All should be thankful that Buddha taught us the great value of parents

in this world of sorrow." Many of the faces in the crowd of onlookers are

not painted in, suggesting perhaps that the viewer should substitute himself

or herself for one of the figures.

A

Zen artist is a master puppeteer too, out in the street using scenes from

everyday life to delight and edify the curious passer-by. Sometimes the moral

is immediately clear, understandable by all in both an amusing and instructive

manner as in Hakuin's and Taikan's paintings. Other times the Zen artist is

more subtle, illuminating only one corner and leaving the viewer to fill in

the rest.

|

There

is nothing subtle about this demon rod (Figure 10) by Shunso Shoju

(1751-1839). Demons wielded such dreadful weapons to beat evil doers as they

fell into hell and this painting is a forceful reminder of the truth: "As

you sow, so shall you reap." The accompanying inscription sums up

Buddhist ethics: "Avoid all evil, practice all good." Rather than

depicting the horrors of hell in gruesome detail, the Zen artist Shunso

presents the case in the simplest possible terms, employing thick brushstrokes

to give the rod a three-dimensional quality and extending the final character

"practice" in the inscription to emphasize the necessity of acting

on one's good intentions. |

|

|

|

Buddha nature has a physical as well as a spiritual side to it and therefore Zen artists depict people (and Buddhas) relieving themselves, passing gas, and making love. In this delightful Zenga (Figure 11) by Ono no Yuren (died 1775), the artist (portrayed as a pop-eyed frog) excitedly watches a young lovely step into a bath; she evidently notices the intrusion of the Peeping Tom and looks back with some disdain. |

The frog reflects to himself, "Although I'm

captivated now, eventually the emotion will subside and my mind will return to

its source." Passions can be dangerous but they also add spice to life;

properly controlled and transformed they can help one attain great awakening.

In keeping with the humorous yet profound theme of the painting, the

brushstrokes are light, bright, and ultimately revealing.

|

Now

a drier subject (Figure 12) by Reigen Eto (1721-1785). The bleached skulls of

warriors and pilgrims who died on the road were a common sight in old Japan,

and Zen artists loved the subject. Reigen's skull painting is a memento

mori: "Turn to dust, ditto, ditto." In spite of the alarming

message, repeated three times to drive it home, the painting is not

frightening. The scene catches the rightness of change, and the foolishness of

being obsessed with the pursuit of fame and wealth; all individual forms

naturally dissolve some day and one should not be afraid of or attempt to

avoid death. Reigen's interesting brushwork is usually quite faint: suggestive

rather than assertive. It also hints at hidden mysteries. What is the strange

shape in the painting's foreground? Could it be a Tantric vajra, with the skull forming the fourth orb? |

|

|

|

Although more research is required prior to unequivocal attribution of this landscape painting (Figure 13) to the renowned swordsman-samurai artist Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), the scene, still on the surface, bristles with an inner intensity associated with that master. |

The cliff jutting out at the left and the tree on

top extend up and out forcefully, unfolding much like a perfectly controlled

sword cut and the ma-ai (the combative distance) between the cliff and the facing

islands is perfectly balanced. Unlike a nanga

landscape painting in which a viewer is drawn into the work, Zen

landscapes project out from the paper, enveloping or even, as in Musashi's

work, penetrating the viewer.

|

|

Contrast Musashi's intense, razor sharp brushwork with the soft lines of Nanzan's charming little sketch (Figure 14). Almost child-like in its simplicity, this is pure, unadulterated Zen art, created spontaneously without artifice or strain. The inscription describes the joys of contemplating nature: "The sound of a bubbling stream at night, the mountain colors at sunset." |

|

Bamboo

is the ultimate Zen plant: flexible yet strong and empty on the inside! This

painting (Figure 15) by Dokuan with an inscription by Daijun (both circa 1800)

is typical of Daitokuji Zen art. With its long tradition of imperial patronage

and as head temple of the tea cult, cultured Daitokuji priests turned out

mostly classical Zen art as we see here. Dokuan was obviously a professionally

trained painter and Daijun, 407th abbot of Daitokuji, added a verse in

impeccable script: "Each leaf [rustles] creating fresh breezes."

Common sense indicates that the wind rustles the leaves but from the Zen

standpoint, it is the leaves that rustle the wind—one cannot occur without

the other. Bamboo remains cool in the hottest weather, "no-mindedly"

accepting the extremes of heat and cold, as it extends steadily upward. |

|

|

|

Kogan

Gengei (1748-1821) here portrays the favorite Zen animal (Figure 16). A bull

fears nothing, and when he sits, he really sits; when he moves, he really

moves—the ideal behavior of a Zen adept. A bull additionally stands for the

mind; uncontrollably wild at first but capable of being tamed, harnessed, and

eventually set free to roam contentedly wherever it pleases. Kogan's solidly

brushed bull-enso is set off against delicate willow branches, a harmonization

of brute force and gentle non-resistance. |

|

When

Mount Fuji is painted by professional artists, the peak is dressed in gorgeous

colors; a Zen Mount Fuji, on the other hand, is austere and created with a few

strokes. In this Zenga (Figure 17) by Yamaoka Tesshu (1836 1888), the greatest

Zen artist of the Meiji period (1868-1912), a handful of brushstrokes create a

lush landscape. The old couple gaze fondly on the lovely scene as the

grandfather says to his faithful wife, "You will live to be one hundred

and I'll live to ninety-nine; the peak of Mount Fuji and the pines of Miho

[are they not beautiful?]". The splendid lines and remarkable bokki bring

the scene to life; a viewer can actually sense the peace and love present in

the work. |

|

|

|

As

mentioned above, anything can be the subject of Zen art. Tesshu's modern

steamship (Figure 18) "Rides the great winds, shattering the waves of ten

thousand leagues." The clock cannot be turned back and one should not

resist change. Developments in technology, too, must be utilized to expand

one's horizons. The free spirited calligraphy flows up and down the paper;

notice the extraordinary bokki in the lines forming the waves and the

ascending smoke. |

|

The

trademark of Tesshu's colorful friend Nantembo (Toju Zenchu 1835-1925), the

last of the old-time Zen artists, was an uncompromising Zen staff (Figure 19).

"If you come forward speaking nonsense, you'll get a good taste of my

staff; if you try to fool me by remaining silent, you'll get a whack!"

was Nantembo's motto. This dynamic staff, painted in his fifties, explodes on

the paper, hanging over the heads of the indolent. The incredible single

stroke of the staff is, simultaneously, abstract and concrete, the key to the

creation of fine Zen art. |

|

|

|

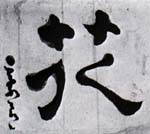

Turning now to the realm of Zen calligraphy—though actually there is no clear distinction drawn between painting and calligraphy—we have a lively ichi (Figure 20) brushed by Ungo Kiyo (1582-1659). Does it represent the koan, "All things return to the One. Where does the One return to?" Or to the "One Truth"? Maybe it refers to the "One Vehicle" of Mahayana Buddhism. Or perhaps the "Oneness" of human beings and Buddha. |

This

single brushstroke resembles a decisive cut of a sword; it begins with a burst

of pure spirit and then tails off into infinity. Even after the brush is

lifted from the paper there must remain a steady stream of concentration; in

both the martial arts and calligraphy, this state is called zanshin

(lingering mind). The bokki is steady and direct, indeed uncomplicated—Ungo

always made his brushwork easy for anyone to read.

Condition is an important factor in collecting Zen art, but collectors should not limit their selections to mint pieces which are, at any rate, difficult to find since so much Zen art was given to children, peasants, and monks and nuns who could not afford to have them properly mounted and stored.

|

|

This "flower" (Figure 21) brushed no doubt for some child by the homeless monk Goryo Dojin (1768-1819) was written on the cheapest paper with borrowed brush and ink but it is, to my mind, infinitely superior to anything I have seen by contemporary calligraphers who only work with the finest materials. |

Even though the paper is disintegrating and torn at the bottom, remounting

would dull the bokki and adversely affect the piece's unadorned charm. In

certain, cases, Zen art should be accepted "as is" without tampering

or trying to restore it.

|

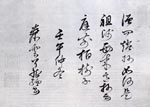

Here is a very rare piece (Figure 22) by a woman Zen master, Ryonen (1646-1711). Ryonen was so lovely that no abbot would accept her as a pupil lest she tempt the other monks; she therefore disfigured her face with a red-hot iron. The brushwork exhibited in this piece is confident and cool; Ryonen was obviously a determined woman. |

|

Technically superior, the spacing of both the lines and

the characters is excellent; the balance, too, is outstanding and the bokki

vivid. The work reproduces a famous koan: "'What is the meaning of the

First Patriarch's coming to the West?' The master replied, 'The oak tree in

the garden."' That is, enlightenment is not confined to the distant past;

it is right in front of your face, if you only look. Also, Daruma's

"coming" was not an isolated event hundreds of years ago; he is

always "coming to the West" in the here and now of Zen training.

|

|

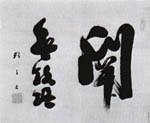

"One-word Barriers" (ichijikan) are unique to Zen art. A large character is brushed to catch the viewer's attention; typically an accompanying inscription is added to reinforce the image. Obaku Zen artists specialized in ichijikan, usually in a horizontal format as we see in this piece (Figure 23) by Tetsugyu Doki (1628-1700). |

It

was composed for a certain Mr Mizumura so Tetsugyu set off the character mizu

(water) to the side and then in the inscription expresses delight at his

host's generosity and the man's efforts to be a good citizen and hard worker.

Such lively, well-balanced brushwork is typical of Obaku artists.

(Incidentally, Zen artists often tried to include the character for water in

their pieces to serve farmers and merchants as a kind of good luck charm; to

bring rain to the crops and prevent fire in the household, for instance.)

|

This

massive ichijikan (Figure 24) by Gan'o (died 1830) is literally a

"Barrier" with this inscription: "The pathless path."

Leave off the agitated ruminations of the mind, press yourself to the limit

(another meaning of kan), and attack

the barrier head on. Since Zen is a pathless path, it can be approached from

any direction; all that counts is effort. The artist's tiny signature suggests

an individual facing immense obstacles; nonetheless, the powerful bokki

inspires the viewer to take the challenge. An interesting feature is the seal

in the upper corner reading bhrum in

Siddham script. Bhrum is the seed-syllable for all the esoteric Buddhist

deities and Gan'o's placement of that mystic sign on his ichijikan indicates

the unity of Zen and Tantric approaches. |

|

|

|

Closely

related to ichijikan are ichigyo-mono (one-line

Zen phrases). Jiun Sonja's (1718-1804) ichigyo-mono (Figure 25) is direct and

to the point: "One who is content is always wealthy". Jiun replaced

animal hair brushes with ones made of bamboo or reed and his calligraphy

appears at first to be rough and undistinguished. Upon further examination,

however, the bokki is found to reflect the high-minded purity of the artist

and the distinctive artlessness of perfectly natural brushstrokes. The

calligraphy still appears as fresh as the day it was put on paper, seemingly

self-formed by some elemental force. The first and last characters extend out

positively, creating a subtle tension that links the middle characters. |

|

The

calligraphy in Nantembo's one-liner (Figure 26) is a bit gruff, similar to the

old fellow himself; even the elongated signature seems to form a staff ever

ready to strike! This ichigyo-mono is more puzzling than that of Jiun: "A

fierce tiger roars, the moon rises above the mountains." The animal cry

of the tiger arises from the raging world of the senses while the inanimate

moon silently shines high above us the key is to settle oneself between the

extremes of matter and spirit, lust and apathy, light and dark, positive and

negative. |

|

|

|

It

is a common misconception that Zen calligraphy is wildly illegible; in fact,

as noted above with Ungo, many Zen calligraphers deliberately make their work

easy to read. This one-liner (Figure 27) by Banryu (1848-1935) clearly states

a well-known Confucian maxim: "A peach tree does not speak yet a path

appears beneath it" (that is, a virtuous person never boasts about

himself but nonetheless attracts admirers). Banryu succeeded Nantembo as the

abbot of Zuiganji in Matsushima. When he arrived at the temple to assume his

new position, he was so shabbily dressed that the gatekeeper mistook him for a

beggar and sent him to the kitchen for food. He was a late bloomer and did not

start painting until his eighties. This piece, brushed in the last year of

Banryu's life, is amazingly sure and steady for an eighty-eight year old man.

Warm and bright, the artist's contentment and peace of mind shines through the

work. |

It

is well understood in the Orient that contemplation of art fosters awakening

no less than sitting in meditation, studying a sacred text, or listening to a

sermon. Zen masters applied their insight to painting and calligraphy to

inspire, instruct, and delight all those who choose to look.